One of the ways in which climate change may be mitigated, and domestic energy

security improved, is to create a new biofuel to power our cars and trucks that

does not rely on traditional petroleum sources. One such fuel, ethanol, is

already widely blended into gasoline in the US; another, biodiesel, is on sale

in many fueling stations as a standalone fuel for diesel engines. However, due

to concerns over the long-term sustainability of current production processes

for biofuels (and for ethanol in

particular),

researchers are investigating a so called “second-generation” of biofuels. These

include fuels that can be made from cellulose (the material that makes up

plants’ cell walls, and comprises most of the mass of a plant) as well as fuels

made from novel feedstocks, such as algae. My research in particular has focused

on one such second-generation biofuel, called biobutanol. Biobutanol has many

technical advantages over ethanol, but biobutanol has not been approved by the

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for use in road vehicles. In a recent

review, Slating and Kesan

discussed the regulatory

hurdles biobutanol must clear to be approved for everyday use.

There are many factors that determine whether the development of a new fuel will

be successful. Some of these factors are engineering ones, and include such

things as power output and energy density. Other factors involve government

regulations surrounding the fuel industry. As an engineer, it is easy to forget

that even if a new fuel is technically better than an existing fuel, it still

must pass regulatory muster before it can be distributed and sold. In the US,

there are two sets of regulations a fuel has to pass before it is considered an

acceptable fuel. As detailed in the paper, these are the Renewable Fuel

Standard (RFS2) enacted in the Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA)

of 2007 and the “Substantially Similar” rule in the Clean Air Act (CAA) of 1972.

The first of these creates a captive market and incentive to produce new

biofuels such as biobutanol, while the second effectively limits the amount of

new biofuels that can be blended into existing fuels, creating a tension that

the EPA is required to balance.

In 2005, the US Congress passed the Energy Policy Act which contained the first

Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS1). This standard mandated certain production

targets for “renewable fuels”, with “renewable fuels” having a very broad

definition. Unfortunately, this standard resulted in little change in the

market, due to the dominance of ethanol produced from corn, which was able to

satisfy the requirements outlined in RFS1. To correct this, Congress enacted the

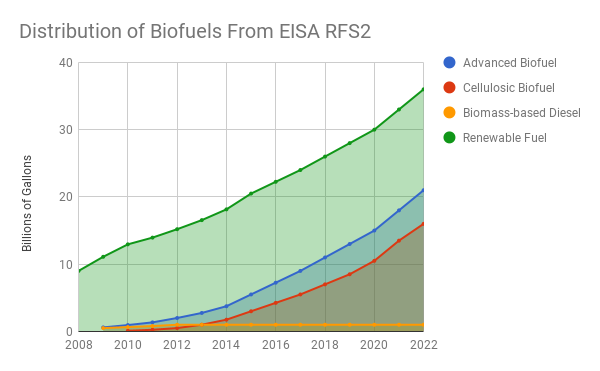

EISA in 2007 which contained the RFS2. In the RFS2, there are four nested

categories of biofuels; in order from most restrictive to least restrictive

definitions, they are Cellulosic Biofuels, Biomass-Based Diesel, Advanced

Biofuels and Renewable Fuels. The definitions are nested such that any fuel that

meets the requirements of either of the first two definitions (i.e. Cellulosic

or Biomass-Based) also satisfies the definition for Advanced Biofuels and

Renewable Fuels. In addition to providing these more stringent definitions, RFS2

also provides yearly targets for biofuel production for each category, with more

restrictive categories making up a larger percentage of the whole as time progresses.

Yearly Targets for Biofuel Production as Specified in the EISA RFS2. Source: Stoel Rives LLP

Depending on the production process, biobutanol could fit into any of the

categories except Biomass-Based Diesel. This means that if biobutanol can be

classified in a more restrictive category than ethanol, it has the potential to

capture a large segment of the market, due to the minimum production mandates in

RFS2. If it cannot meet the more restrictive definitions, ethanol may fulfill

the requirements satisfactorily, removing the market for biobutanol. It is

unclear as of this moment which production process for biobutanol will prove to

be commercially viable (leaving aside the regulatory issues), and therefore it

is uncertain which category biobutanol might fall into.

Once a new fuel such as biobutanol is categorized according to the RFS2, it

still can’t be introduced into road vehicles without the approval of the EPA

under a second set of regulations set forth in the CAA of 1972. In the CAA,

Congress outlined the “Substantially Similar” principle, which states that any

new fuel cannot be sold unless it is “substantially similar” to the fuel used by

the EPA in its tests of road vehicles. If a new fuel cannot be fit into the

substantially similar protocol, the company must apply for a fuel waiver for

that fuel, or try to apply a previously granted fuel waiver to their fuel.

Biobutanol, therefore, has three potential paths to take through the Clean Air

Act - to comply with the substantially similar rule, as it is currently set

forth by the EPA; to try to fit into an existing fuel waiver; or, to apply for a

new fuel waiver. The easiest path to take would be to follow the substantially

similar rule, which limits the weight percent of oxygen allowed in the fuel.

However, this would limit the amount of biobutanol which could be blended in

gasoline to about 12%. If a company wanted to try to fit into an existing fuel

waiver, they could attempt to pass through a loophole in a waiver that was

intended for methanol; this could allow up to 16% biobutanol blended with

gasoline. However, there is no guarantee that the EPA would allow this fuel

waiver to be used for a fuel for which the waiver was not granted. Finally, a

company could choose to apply for a new fuel waiver; this process could take

years, and according to the analysis in this paper, has only a small chance of success.

With the regulations as they stand, the authors assert that revised regulations

are appropriate, so that society can reap the benefits of cleaner burning fuels

in the very near future. They suggest two changes that could considerably speed

the regulatory approval of new fuels. The simplest would be for the EPA to issue

a new “Substantially Similar” rule, allowing the use of higher blending amounts

of biofuels (such as biobutanol) which have been shown to reduce regulated

emissions. The authors’ other suggestion is for Congress to modify the Clean Air

Act, so that the EPA is forced to consider new fuel waivers in a more timely

manner, especially for fuels that satisfy the RFS2 mandates. Since this may not

occur in the near future, the authors’ strongly recommend the EPA to create a

new “Substantially Similar” rule.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1757-1707.2011.01146.x