In the race to stop global warming and improve energy security, one of the

strongest initiatives politicians can rely on is regulating the energy

efficiency of an economic sector, such as manufacturing, energy generation, or

transportation. Increasing energy efficiency allows us to “do more with less”,

implying that increasing energy efficiency is always a good thing. Not so fast,

claim some economics researchers from the UK. In a study published in 2009, they

found that if energy efficiency of the Scottish economy were increased, the

energy consumption of Scotland would increase as well. The authors attribute

this to two effects, called rebound and backfire.

Rebound and backfire are well researched economic effects, especially as they

relate to the consumption of energy. Put simply, rebound is the case when an

increase in energy efficiency does not cause an equal decrease in energy demand.

Backfire is a special case of rebound where an increase in energy efficiency

causes an increase in energy demand. Prior to this work, there had been several

empirical studies of rebound and backfire in the world economy, but very few

groups had studied the effects systematically through computer simulations. In

the current study, the research group has used a computer program called

AMOSENVI to conduct their simulations.

The AMOSENVI code is a rather complicated beast. It takes as input the specified

sectors of the economy, a percent increase in energy efficiency, and how the

different sectors of the economy interact, as well as how the regional economy

(Scotland in this case) interacts with the economy of the rest of the UK and the

rest of the world. AMOSENVI assumes an initial equilibrium in the economy. When

a simulation is run, the program applies the percent increase in energy

efficiency as a beneficial supply-side shock to the economy. Then it calculates

the effect of this shock by moving forward in time. The indicators from the

simulation use Scottish energy consumption, both in terms of electricity use and

use of non-electricity energy sources, to determine the effect of rebound or

backfire, as well as reporting the ratios of GDP to energy consumption and GDP

to unit of CO2 emissions.

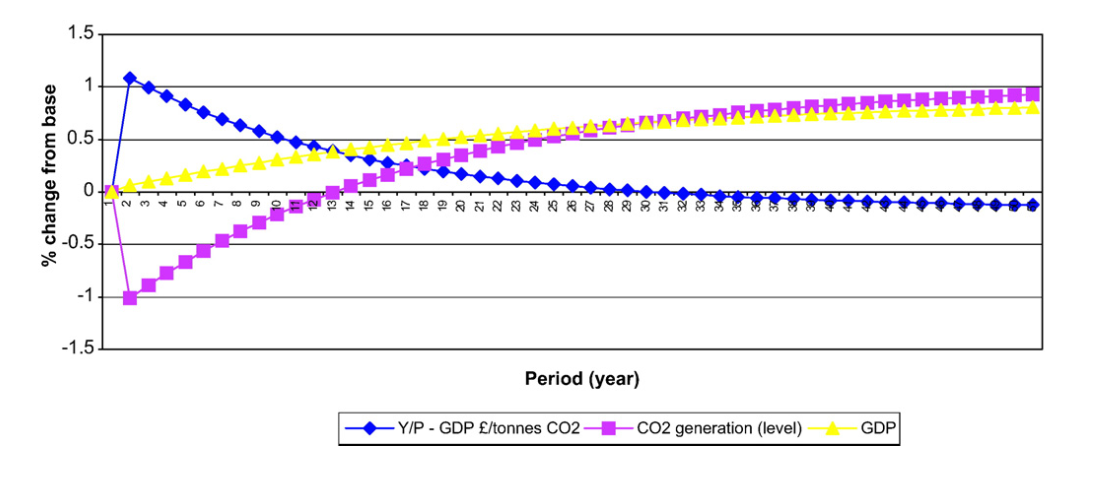

The authors studied the case of 5% improvement in energy efficiency, and varied

the other inputs systematically. In the short and medium term, for all of the

cases, they found significant rebound in electricity consumption and total

non-electricity energy consumption - that is, although they found a decrease in

energy consumption, this decrease did not mirror the increase in energy

efficiency very well. In the long term, for all the cases studied here, the

authors found that increasing energy efficiency actually backfired, and

increased energy consumption! In addition, after about 30 years simulated time,

growth of emissions of CO2 began to increase faster than GDP, another negative

indicator. These results seem to indicate that simply increasing energy

efficiency of sectors is not sufficient to reduce global climate change in the

long term.

Impact of a 5% Increase in Energy Efficiency on Environmental Indicators. Source: Hanley, et al.

Finally, the authors note some of the deficiencies of their study; first, they

only considered the regional economy of Scotland, and larger economies (such as

the whole UK) would experience different effects; second, there may be

trade-offs between local and global environmental concerns resulting from

improvements in energy productivity; third, the information presented by the

indicators they have chosen (i.e. ratios of GDP to energy consumption and CO2

emissions) is not a complete description of the effect of the economy on the

environment. The authors conclude by noting that a combined approach of several

policy initiatives is necessary to produce substantial change in the global

environment, and measures which proclaim to be beneficial in the short-term may

have long-term unintended consequences.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.004